When talking about muscular attachments, it’s important to know and understand the difference between the origin and insertion. They are not interchangeable and have totally different meanings, though you can say muscular attachment or attachment site and be talking about either the origin or the insertion.

What’s the difference?

When a muscle contracts, the origin pulls the insertion closer. Always! Muscles pull. The origin is the fixed point that doesn’t move during contraction, while the insertion does move. Your bones are the levers and your muscles are the pulley. Basically, we are all super complex puppets on strings. To explore this further, let’s take a look at the rhomboids.

Rhomboids Minor and Major

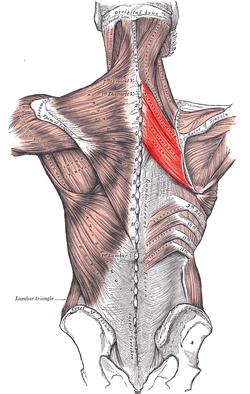

Firstly, there are two rhomboids and they’re both deep to the multidirectional fibers of the trapezius. Rhomboid minor sits on top of, or superior to, its larger counterpart rhomboid major. Minor originates on the spinous processes of C7 and T1 while major originates on the spinous processes of T2-T5. You can pretty easily feel for T1 on yourself, it’s just at the base of the posterior neck and it bumps out a little bit posteriorly. The transverse processes stick out to the sides while the spinous processes, which we are talking about here, stick out and a bit downward posteriorly. They remind me of a stegosaurus. It’s from these little posterior projections that both rhomboids originate.

Back to rhomboid minor, it inserts on the upper portion of the medial border of the scapula, across from the spine of the scapula. The insertion for levator scapula is right there too and is easily palpable on yourself or someone else. Rhomboid major inserts on the medial border of the scapula as well, basically between the spine of the scapula and the inferior angle of the scapula. The actions of the rhomboids are to retract or adduct the scapula, elevate the scapula and also downwardly rotate the scapula.

WHOA, WAIT.

How does a muscle that elevates the scapula downwardly rotate it as well? If you look at the direction the fibers run, they’re on a bit of a downward angle going from the spine to the scapula. Because of this, when the muscles contract, they have the pulling capacity to draw the shoulder blades closer together. Downward rotation can be a tricky one because the scapula is the only bone in the body to do it, but we’re referring more specifically to the movement of the acromion, which is the flat bony process at the lateral end of the posterior scapula. When the rhomboids contract, they have the ability to tilt the acromion downward. It’s a slight action but it’s there nonetheless. Lastly the rhomboids can also elevate the scapula as a whole. Every time the muscle contracts (concentrically, that is, but that’s another post for another day), the origin says ‘come to me’, and so the insertion does. This is true for all the muscles in the body.

When studying anatomy, learn to look closely at the direction of the muscle fibers, and determine which end is the origin and which end is the insertion. That information will take you a long way in figuring out what actions a muscle can do.

ANOTHER EXAMPLE

Let’s look at a neck muscle- the sternocleidomastoid, or SCM. It has two heads which means it originates in two spots: the top of the manubrium (sternum) and the medial third of the clavicle. Its insertion is up behind the ear on the mastoid process and the outer portion of the occiput. When both the left and right right SCM contract together, the origin (which is down on the clavicle and sternum) pulls the insertion toward it to create neck flexion and also assist to lift the rib cage to make more space for inhalation.

My hope is that this makes sense but if you don’t understand and would like to, please send me an email and I’ll break it down even more! If you’re teaching and get confused about what’s the origin and what’s the insertion, you can simply say attachment. But do trust yourself! If you take a moment to think about how the body moves and works, and you know the origin is fixed and the insertion moves, you can likely figure it out for yourself.