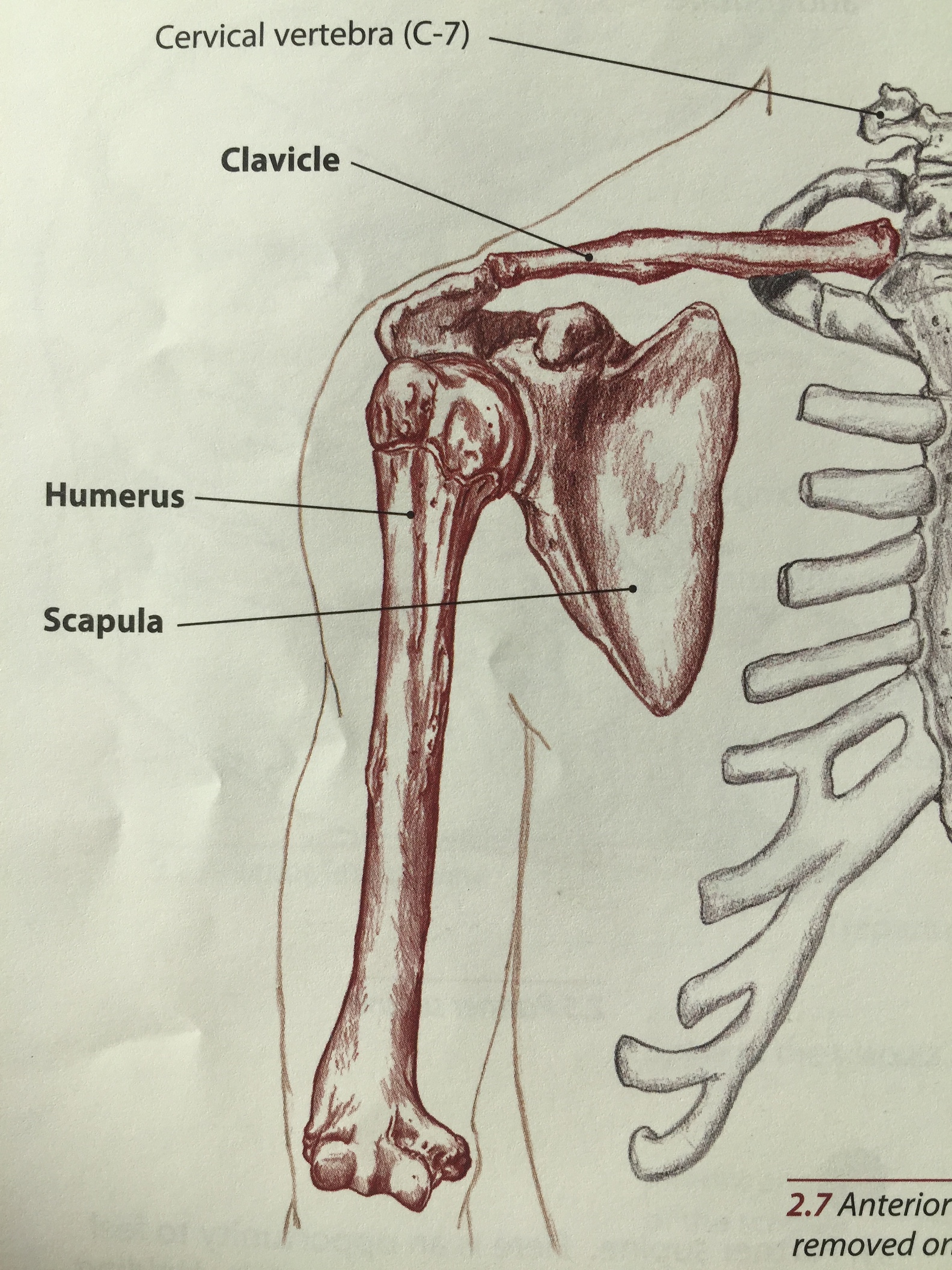

The rotator cuff is a group of deep stabilizing muscles that all start on the scapula and stop on the head of the humerus. As a whole they work together to hug the head of the humerus into the glenohumeral joint, but in addition to that the muscles all have their own unique actions based on where they originate and insert. A review of the bony anatomy of the scapula and humerus may be helpful before reading this post.

There are four muscles that make up the rotator cuff. First, a brief overview of everything the shoulder can do at the glenohumeral joint. Click here for a definition of these terms.

Adduction

Abduction

Horizontal adduction

Horizontal abduction

Lateral rotation

Medial rotation

Flexion

Extension

The muscles of the rotator cuff medially and laterally rotate as well as abduct the shoulder. They also all work together to stabilize the head of the humerus in the glenoid fossa.

What does what?

Infraspinatus

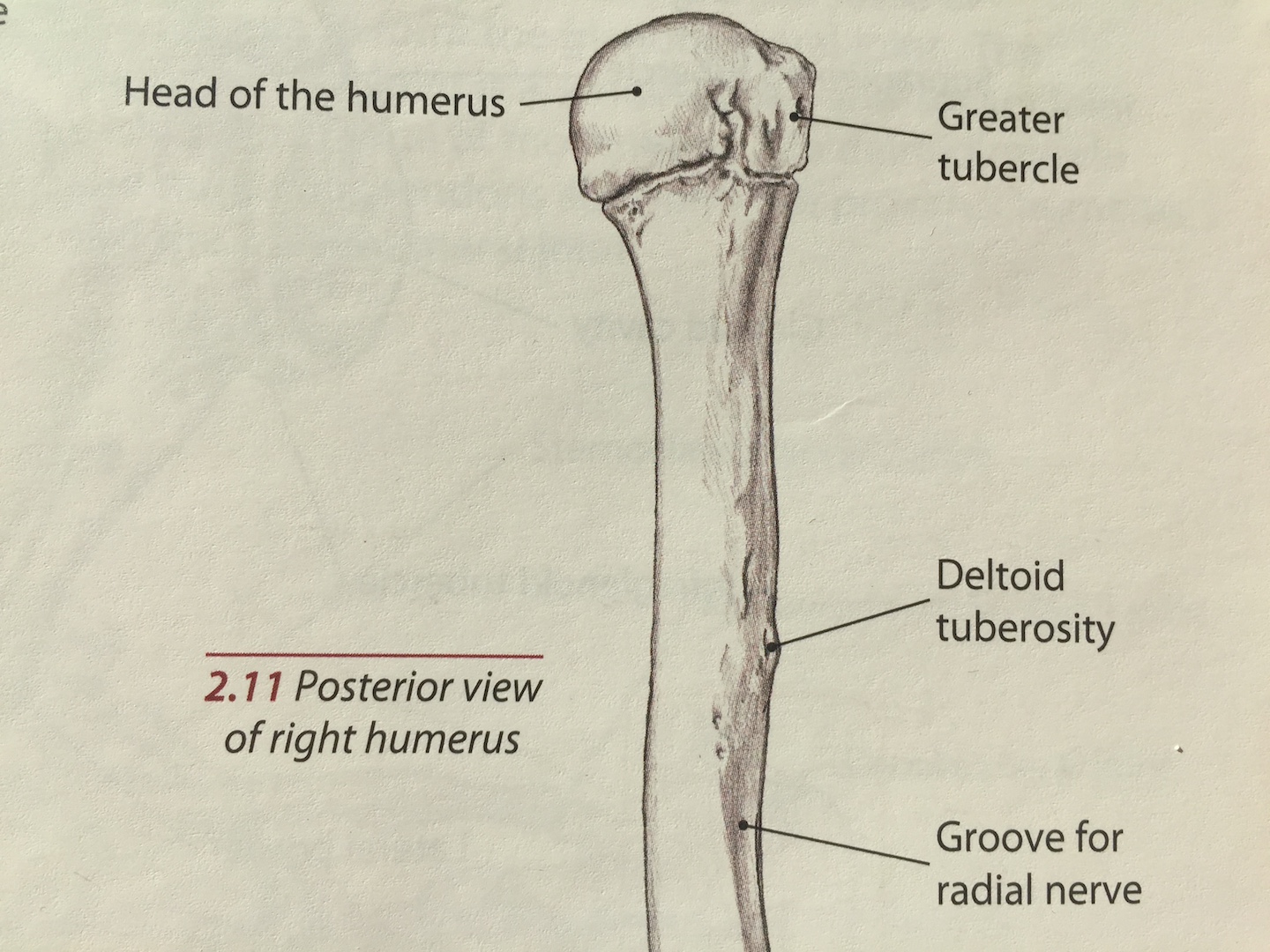

The infraspinatus muscle is a lateral (external) rotator. It originates on the posterior scapula in the infraspinous fossa. Infraspinous means inferior to (below) the spine of the scapula. That whole space is the origin of the infraspinatus. From there it inserts on the posterior aspect of the greater tubercle of the humerus. When the insertion comes toward the origin during contraction (the insertion always comes toward the origin as the origin is the fixed point), it creates lateral rotation of the shoulder. If you’re reaching your arm overhead to brush the back of your hair, your shoulder is laterally rotated. The top arm in gomukasana (cow’s face pose) is also in lateral rotation.

Teres Minor

Teres minor goes with infraspinatus in the same way that teres major goes with the lats. The two muscles share the same actions and therefore the teres minor acts as an assistant to its larger counterpart, the infraspinatus. Teres minor originates on the upper two thirds of the lateral (outer) border of the scapula and also inserts on the posterior aspect of the greater tubercle of the humerus. It shares the same jobs as the infraspinatus: stabilize the head of the humerus in the glenohumeral socket and laterally rotate the shoulder.

The term teres translates from Latin to mean rounded or tube shaped. I love to learn little things like that because they help me remember either where a muscle or structure is, what is does, something about its shape or size, etc. Learning the language is hugely helpful. You can also remember which teres muscle assists which larger muscle like this: The latissimus dorsi is a huge and superficial muscle, so it needs the major helper. Infraspinatus is a smaller, deeper muscle and so it gets the minor helper.

Subscapularis

The subscapularis is a mirror to the infraspinatus. It originates on the anterior surface of the scapula in the subscapular fossa and inserts on the lesser tubercle of the humerus. This is the only one of the four rotator cuff muscles that inserts on the lesser tubercle rather than the greater. In addition to helping to stabilize the humeral head it also medially (or internally) rotates the shoulder. If you take your right arm out to the side and use your left hand to grab the back flap of the armpit, and then press your right hand into your belly you will feel subscapularis engage. During gomukasana pose with the arms, the shoulder of the bottom arm is medially rotated. When the hands are clasped behind the back, the shoulders are medially rotated. The deeper subscapularis medially rotates the shoulder with help from the more superficial teres major, latissimus dorsi and anterior fibers of the deltoid.

Supraspinatus

The supraspinatus originates in the supraspinous fossa, which means superior to the spine of the scapula. The fossa is deep, and this muscle sits underneath of the fibers of the upper trapezius and the deltoid. The long head of the biceps brachii is right here too. It inserts on the greater tubercle and abducts the shoulder. When I first learned about this muscle, I learned that it was just an initiator of abduction (taking the arm away from the body), but after more reading I’ve learned it’s more than just an initiator. It is involved in shoulder abduction up to about 90 degrees. The supraspinatus, like all rotator cuff muscles, assists in stabilizing the head of the humerus as well as abducts the shoulder at the glenohumeral joint. When you raise the arms for a sun salutation, the supraspinatus is working to lift the arms away from the body. When the arms are outstretched in warrior two, the supraspinatus is working.

Biceps Brachii

I wasn’t going to talk about this one yet since I haven’t made a post on the bony anatomy of the radius and ulna, but I can’t help myself. I think it’s quite relevant here, so here is a brief introduction.

Biceps means two heads, so to refer to the biceps brachii as simply the biceps, you could technically be talking about any two headed muscle on the body, particularly biceps femoris which is the two-headed outer hamstring muscle. Brachii means arm (specifically the humerus), so biceps brachii means two-headed muscle on the upper arm.

The long head originates at the supraglenoid tubercle (the bony prominence above the glenoid fossa), while the short head starts on the coracoid process (beak-shaped bony prominence on the anterior scapula). Before becoming the meaty belly of muscle on the anterior surface of the upper arm that probably nearly everyone could point out, the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii passes through the glenoid fossa as well as the intertubercular groove. The intertubercular groove is the space between the insertion points of the rotator cuff muscles. The glenoid fossa is, of course, the shoulder socket. Looking at the photo below you can see how interrelated the rotator cuff and the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii really are.

It plays a role in shoulder flexion but an even bigger role in supinating the forearm. It also flexes the elbow. More to come on the biceps brachii as well as bony anatomy of the radius and ulna in a later post.

Side view of the right shoulder without the humeral head. Clemente Anatomy.