While it’s true that the fascia is one big continuous and completely connected piece of tissue, it looks and acts differently depending on where it’s located in the body. In order to gain a better understanding of the fascial system as a whole and also have it be less overwhelming, we’ll break it down into more digestible bites.

Just beneath your skin there is a layer of fatty tissue that provides the body with necessary insulation, blood and lymphatic flow and energy storage. Just beneath that is the superficial fascia. It anchors the skin to the tissues and organs below and is rich in blood and lymphatic vessels, nerves and some general sensory receptors which I’ll describe in detail in a later post. This thin and fibrous but highly elastic layer is classified as loose connective tissue. In this case loose just means it lacks any regular pattern or strong organization.

Unlike the superficial fascia, the deep fascia is dense and well-organized. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the coolest layer of fascia because of the incredible and stunningly beautiful way it surrounds, supports and separates yet also connects every single structure in your body. The deep fascia is rich in sensory receptors that are sensitive to things like pressure and movement, which I will also cover in detail in another post. First let’s look at the anatomy of a muscle. Understanding the fascial anatomy of a muscle is essential for truly understanding how yoga and massage create change for people and actually really “work”.

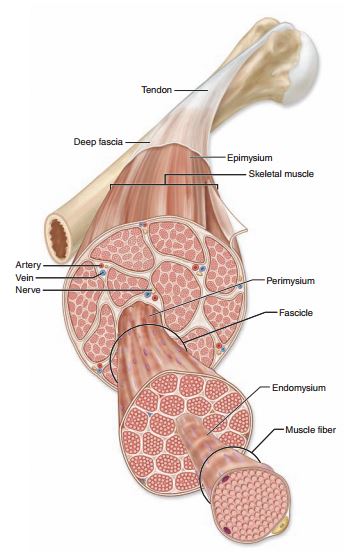

Let’s consider a muscle from the outside in, or anatomically speaking, superficial to deep. Every muscle as a whole is wrapped in a sleeve of fascia called the epimysium. Epi- meaning on and my- meaning muscle. Epimysium means on the muscle.

Within each muscle are groups of muscle cells that have been bundled together into what’s called fascicles. Each fascicle is wrapped in its own layer of fascia called the perimysium. Peri- meaning around and my- meaning muscle. Perimysium means around the muscle.

Each individual muscle cell also has its own layer of fascia called the endomysium. Endo- meaning within, my- meaning muscle. Endomysium meaning within the muscle.

Each of these three layers comes together to form the tendons that connect muscle to bone. The layer of fascia that surrounds each bone is called the periosteum.

In part two we’ll look at the fascial layers that surround the brain, nerves and organs as well as the anatomy of a nerve.